YOU CALL IT A SEX HOUSE; I CALL IT HOME

You Call It A Sex House, I Call It Home: BUST true story by Lila Donnolo

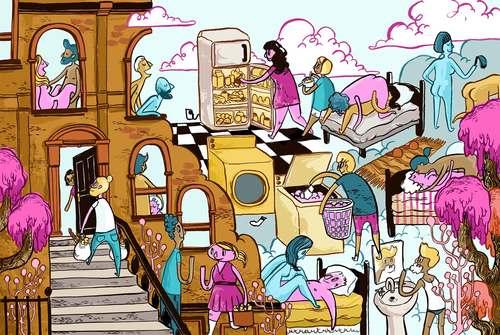

It’s 11 a.m. and I can hear spanking. Somebody’s happy, I think to myself, then mentally pinpoint the floor (third), the bedroom (the sound designer’s), and the lover (his girlfriend). Curiosity quenched, I turn my mind back to writing. It’s morning at Hacienda Villa, and approximately 15 percent of the residents are fucking.

I’m a founding member of this sex-positive intentional community, established in 2014 and housed in a gut-renovated brownstone in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The building was bought and restored by an investor and benefactor of sex-positive culture who wishes to remain unidentified, and the community was co-founded by Kenneth Play, our resident sex educator. The Villa is currently home to 14 members in 14 private bedrooms ranging from $750 to $1750 a month, with six residents on the third floor, five on the second, and three on the first. Amenities include three bathrooms on the second and third floors and private bathrooms on the first, a hot tub gazebo in the backyard, the N.Y.C. holy grail (a washer/dryer), and someday, when construction finally ceases, a basement event space that will host sex-ed seminars and erotic art installations.

The only way to become a member of the Villa is to already be known to our sex-positive community, or to be friends with someone who is. I found out about it through a friend of a friend, came in for an interview with Kenneth, and was one of the first to move in. After some growing pains, our new member process now includes a 30-day trial.

Many imagine the Villa to be a wild place of everlasting orgies where you wouldn’t want to touch the doorknobs. In truth, the orgies are minimal and generally confined to one person’s room. And since the cleaning ladies visit once a month, the doorknobs are perhaps cleaner than in most other buildings in the borough of Brooklyn. The Villa is typically quiet, or as quiet as it can be while housing an inspired DJ in a construction zone near an above-ground train in Brooklyn. Our house rules vary on a floor-by-floor basis—my floor has agreed to quiet hours from 12 a.m. to 8 a.m., knocking/returning later if someone’s bedroom door is closed, and contributing in some way to maintain the common area.

Sex-positive does not mean that we have sex indiscriminately, or that we’re all fucking each other. (We actually have a policy against having sex with roommates, and that extends to all the floors.) It means we embrace a vast array of sexual interests and lifestyles among consenting adults. We believe sex is essentially good. We celebrate it. Sex is normal! Sex is healthy! Sex is an appropriate topic of conversation! Sex-positive means no slut shaming (and, in fact, no shaming of any kind). There are so many reasons why one might choose to engage in sexual play – friendship, bonding, romantic love, recreation, intimacy, healing, intrigue, work, performance – and when chosen deliberately in sound mind, they are all equally valid.

While the Villa welcomes those who practice polyamorous lifestyles, we are not a “poly” house. As of this week, five of the 14 “Villans” are engaged in some form of polyamory. Everyone has a different arrangement, and their relationships change and evolve. The sound designer used to have two serious girlfriends, but one of them broke it off, and he’s remained with his other partner exclusively for the past few months. The social worker has one primary partner and two regular lovers who have partners of their own. The photographer is monogamous. The DJ is dating.

As for myself, the sex I’m having here is no more frequent than when I was dwelling in non-intentional railroad apartments, but the quality of the sex I’m having has improved remarkably, because living here is a permission slip and an education. Having a sexpert like Kenneth in-residence as house manager means I can go to him for advice on everything from compassionate communication to how to effectively use an njoy Pure Wand dildo.

We Villans share an interest in returning to a more tribal, village-dwelling way of life, without leaving N.Y.C. I’ve wanted to live in an intentional community since I first visited one in Ashland, OR, in 2008, but I didn’t think it was possible in this city. Since I don’t come from a particularly close-knit family, I have sought family everywhere, and this is the place where I’ve found it. Last winter was the first that I didn’t experience seasonal depression, and it was because of my roommates’ kindness on brutal February days. I know that if I’m sick, someone will get me medicine. If I’m crying, someone will hold me until it passes. I am called on to do the same for others, and I’m glad for it.

Living here is a balm for the deep shame and secrecy I’ve experienced surrounding sex in our culture. Since sex isn’t taboo at Hacienda Villa, nothing is. We can talk about politics. We can talk about love. We can talk about death. We can get spanked at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday and then breeze into the kitchen saying, “Good morning!” In that way, it is wilder than your average apartment, but that’s only because we’re not keeping our kinks secret. We want everyone here to have a great sex life—and for us, that begins right here at home.

Dear One,

In 2008, I moved to Portland, Oregon. I was twenty-five.

Since the time I was 7 years old, and played Toto (yep, that’s the dog!) in a Recreation Center production of The Wizard of Oz, I wanted to be on Broadway. I wanted to be a movie star. I wanted to walk the red carpet in a fabulous gown. Those were my childhood dreams, and in 2008, I wasn’t making any progress in their direction. I didn’t have an agent. I didn’t go to auditions. I wasn’t making my own work. I was just a yoga teacher.

I’d just returned from my first cross-country road trip, and suddenly it felt as though all the doors I’d counted on in New York were closing in my face. Right when I got back, my boyfriend broke up with me. In Prospect Park. My AcroYoga teaching partner didn’t give me our class back. She was teaching with someone that she loved more and she didn’t want to give it up. I was still dragging myself out of bed at 5am to teach 7am classes. I didn’t like my roommate and I was living in this crummy railroad apartment. I had to walk through his bedroom to get to the bathroom, or else put on pants and exit the apartment to walk through the hallway to get there.

I asked myself this: If I’m not pursuing my dreams anymore, then why am I here? New York City is such a struggle! I’m scraping to pay my rent! I debate myself over whether I can buy a tea so I can sit in the coffeeshop and write for a few hours! The air is unsavory, and the entire city runs on an undercurrent of anxiety. And it’s just so hard. In so many, many other ways.

I decided that I had failed at those dreams, and spent a few months admitting that to myself. Even though there’s no statute of limitations on becoming a Broadway actress, at that moment, I had to relinquish that hope; I had to accept this little death in order to allow myself to move across the country. Because if I wasn’t pursuing my childhood dreams, then at least I could live in a place where I wanted to breathe the air, where my days would be more genteel, a place with gardens and houses that lay close to the ground.

I moved to Portland for two years. To the day.

There, surprisingly to me, I still struggled paying my rent. Yoga teachers were paid so poorly in Portland and it was challenging to get enough work. But I loved the city and its bicycles and its slower-paced culture and the blooming things everywhere, and all the all the all the green.

I didn’t have a car, so I was often biking in the rain, and I never spent the money to buy proper waterproof gear, which meant that I was forever slightly soggy or asking for rides, and this made me cranky. The grey skies and the air pressure were tough on me, as a person with a tendency towards melancholy to begin with. Depression and anxiety run in my family on both sides.

After the initial delight of moving across the country and delving into the tango world faded, I realized that I felt grey for much of the year in PDX. Summer would come around like a grand reprieve, and suddenly Portland was like Pleasantville and everybody would be smiling and I would be dry and the sunglasses would come out and my whole perspective would change. But summer was brief. I knew I couldn’t live in a place like that indefinitely, not in the way that I was, at least. So after two years, I took off.

Before I did, it was the fall of 2010, and I was feeling very blue. Blue AND grey. I didn’t know what to do with myself, how to progress, where to go, what to devote myself to. In the fall of 2010, when I asked myself what I really wanted to do with my life, the only answer I could come up with was, “I want to travel.”

“Ok,” I said to myself, “Why aren’t you traveling? That’s why you became an AcroYoga teacher, right? So you’d have this valuable, portable skill. Loads of your colleagues are traveling full time. Why can’t you?”

“I’m scared,” I answered myself.

“What are you scared of,” I asked.

I searched myself, and I found an answer that embarrassed me. READ MORE…

BRAVE ON THE ROCKS, OR, CHOOSING TO OPEN WHEN YOU WANT TO SHUT BUT YOU KNOW IT WOULD REALLY BE BETTER IF YOU OPENED

horizontal in Baltimore, Maryland on the sidewalk outside The Charmery in Hampden. Soulful October 2017.

When I was a teenager, and nearly the only place for me to hang out in suburban Florida was my local Barnes & Noble, I found a book called spilling open.

Sabrina Ward Harrison, at the age of 21, published excerpts from her sketchbook, a compressed collage full of self-portraits and color and painted photographs and tender wonderings and frank doubts.

I have carried this book with me through (I counted them on my fingers not so long ago) eleven moves. From high school to dorm room to share to first apartment, across the country to house to apartment to house, back across the country to storage in Dad’s garage to apartment to apartment to community. It still occupies a place of honor in my postage stamp of a room. It’s been four years and counting that I’ve lived at Hacienda Villa. I was sixteen when I found spilling open.

It wasn’t until my 30s that I picked up her second book.

I’m 35 now.

It’s called brave on the rocks.

The narrative begins after the success of her first book, which surprises and overwhelms, more than delights her. The unexpected attention fills her with increasing self-doubt and the pressure to live up to her own image … to the point that she gets an ulcer.

At the top of the book she reprinted a letter from her father. He reminisces about their barefoot walks together along secret trails when Sabrina was a six year-old child.

“The thing about bare feet,” he writes, “is that they move easily and quickly over mud and dirt and sand and grass but tend to hesitate before a barrier of pointy, sharp-edged gravel.”

That summer, her grandfather re-paved his driveway. The first time they approached the edge of it, barefoot, Sabrina held her arms up for a “special carry.”

“But in this situation something told me not to pick you up.” […] “In my mind’s eye I see myself hunker down in front of you and explain the rules of barefoot travel. I told you paths are not always smooth and familiar like the Indian Trail or the good ones out on Pine Ridge. Sometimes there are rocks on the trail and the only way to cross them is to be brave. As I sit here so many years later, I smile when I remember how proudly you walked over the gravel that summer. Whenever we came back to the cottage by way of the Frog Bridge, you would get breathless and boldly announce how you were going to be ‘brave on the rocks.’ Love, Dad.”

I have had many opportunities over the past couple of years to open when I wanted to shut.

***

I don’t use the word “friend” lightly. Friends are people you show up at the hospital for, and who show up for you. Ones you can call in the middle of the night with a crisis of the heart. Ones who bring you rhinestones, ice cream, and pictures of cats when you are in need. And sometimes — much less often — ones for whom I open when I really want to shut. Those are my friends.

I imagine most of us could count these folks on two hands.

The ones you’re willing to have the difficult conversations with. Genuinely hard talks. Where the words don’t come easy. Where you risk the truthfullest truth. The ones where you say, “I don’t think this is the man that you should marry,” or, “I think you need professional help,” or, “Your behavior towards your lovers looks like emotional abuse,” or “I know you’re angry with them, but you didn’t actually make a clear request.”

My friend Julene calls these talks “come to Jesus meetings.” They are one of my primary friendship barometers.

We’re not trained for uncomfortable conversations anymore. Maybe we never were. But I think it’s worse now. It’s got to be. Most of us barely make eye contact these days. We’re out of practice in both social niceties and face-to-face honesty, so every sticky conversation carries the gravitas of an intervention.

I have to really, really care to stage an intervention.

In college, I was kind in love with a guy who was sort of my boss. He was a couple of years ahead of me in school. I did my work study gig at the organization he founded. I remember him telling me once, that someone he admired told him once, that success in life is directly related to one’s ability to have uncomfortable conversations.

I believed it.

I still believe it.

I think about it all the time.

Three years back, I knew I needed to have a “come to Jesus meeting” with my friend. In person. In Portland. I was visiting. I wanted to see her as soon as I arrived, but she delayed. Then postponed. Then delayed again. Our relationship had been shaky at best and distant at most for a couple of months, and I felt in my digestives a rumble of worry and an undercurrent of anxiety over it all.

She was two hours late to meet me.

At first she said she’d be a little late, because her morning hike took longer than expected. Then she pushed it back an hour. Then she said a lot of resistance was coming up in regards to our meeting, and that made her unable to show up on time.

I asked if that was her way of cancelling.

She said “No, no, I’m coming.” Then it took another hour for her to arrive.

During that second hour, I had a come-to-Jesus meeting with myself. READ MORE…

“DONE NOTHING WITH MY LIFE”

horizontal in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on my trusty borrowed steed. Photo by Julie Savage-Lee

I have always been incredibly hard on myself. These days it most often takes the form of “I’m 35 years old and I’ve done nothing with my life.”

In years past, it was about feeling ugly, or not being “the best” at anything, or not being able to make a living in the career I trained for. (What does that even mean, anyway, the “best?!” Skills are always fluctuating, and particularly in the fields that I am a part of, “best” is entirely relative! Why do I still hear my mother’s voice in my mind, saying, “You’ll never be the best at anything, but you won’t be the worst, either.”??)

This past year, though, I finally did something that felt like doing something. Something that felt like living into my purpose of cultivating intimacy in all its forms. I started this podcast, and, even though it wasn’t “perfect” and I have plenty to learn about recording and mic technique and editing and sound design, for the first time in my life, I didn’t just abandon my project when it got hard. For the first time I actually believed that what I had to offer was so valuable that it wouldn’t matter if the sound wasn’t studio quality or I didn’t have a gold-standard radio mic. I felt, truly deeply, madly, that I had an obligation to release this work into the world, because it had the potential to inspire.

Things were going well! I got a great boost in the beginning, I reached 20,000 downloads in a few months, and people were saying lovely things. Telling me that because they were listening, they had conversations with their lovers that they never otherwise would have broached.

I got excited. I went on that solo cross-country road trip to record more episodes. See visual aid, above. I spent most of my savings on it, traveled for two months with full autonomy, catering entirely to my intuition, my curiosity, my whims, my delight, the kindness of strangers, and my penchant for beauty. I drove 15,000 miles. I listened to books and podcasts. I sang to myself. I worked things out. I chatted on the phone over the rumble of the road. I screamed. I cried. I wailed. I yelled. I was quiet with myself and loud with myself. It was an ambivert‘s dream: I spent hours with myself, recharging, and by the time I craved human company, I would arrive someplace and connect with other humans. Before I became too full with social contact, I got back into the car and breathed the deep breaths of chosen solitude.

I circumnavigated the United States for two whole months, by myself, and I felt so free and so happy.

But when I got back on December 1st, my fatigue caught up with me.

I’d been feeling fatigued for … years, I think. I had ruled out thyroid, anemia, sugar addiction, and environment. I figured that if two months of freedom on the road didn’t cure me, then I’d go seek some help for my mental health.

I didn’t manage to release episodes after the first couple of weeks on the road. It was too much to devote the time I require to edit an episode. All the hours of driving and figuring out where to stay and exploring and experiencing and recording. I decided to give myself over to that. I did feel less tired while I was on the road, but it was still there, like a downward tug on my body, like gravity was heavier than gravity for me.

It just got worse and worse when I got back to New York. I got so depressed that I didn’t produce any episodes at all for another two months — even though I had 14 new recordings in the can, and 4 from before I’d left! Eighteen recordings I was sitting on! It felt awful. I felt awful. It got to the point where I was binge watching TV nine hours a day and/or staring at the ceiling of my bedroom (where some mosquitos once died a horrible death and I have forever after forgotten to bring something up to the loft bed to clean them off so I wouldn’t be staring up at them wishing I had the energy to get up and wipe off the damn ceiling, but entirely unwilling to actually do it).

For a few weeks, I only managed to drag myself out of the house to teach my classes. I only managed to do what was required for basic survival. I did not write. I did not edit. I did not make art of any kind. I couldn’t even manage to lie down and do podcast work on my computer. I felt hazy and detached, like my thoughts were molasses. I wasn’t even horizontal with myself.

I was sleeping ten or eleven hours a night and waking up feeling as though I’d slept four, yet I didn’t want to sleep any less.

I had always chalked up my blues to an artistic temperament. I didn’t ever want to take medication, because that would mean that I was like my mother.

My mother is bipolar. READ MORE…

RAISE THE ROOF, OR, THE UPPER LIMITS PROBLEM

Hopeful Lila at The Confetti Project’s Open Studios. Image by Jelena Aleksich. June 2018

A couple of years back, I had this unfamiliar — yet nearly intelligible emotion. It was a tip-of-the-tongue sort of feeling. Like an aroma I couldn’t quite place. A dream smell, maybe. I remember something like it the first day I opened a car door in Nevada.

It was 2008. My first cross-country road trip. We stopped on the shoulder of the highway to pee. (I know, I know, inadvisable!) As soon as I stepped out, I smelled this … sweetness on the air.

It arrested me.

I didn’t know exactly what it was — but it seemed as though I almost did, even though I was sure I’d never smelled it before. I stood still and I breathed it in.

“That’s delightful!” I said. “That’s delicious! What is it?”

It turned out to be sage. Sage growing lush and rampant on the side of the highway. Flourishing and wild and un-tended.

***

The unfamiliar familiar feeling … it had a quality of pause that felt like the sage. It arrested my momentum. It was such a faint slow rhythm that I had to physically stop myself still, in order to discern what I was feeling. Then I had to get quiet enough on the inside to listen to the tender bird of an answer.

The answer was: contentment.

Holy shit, contentment?!

I’m reminded of the Nathaniel Hawthorne quote, “Happiness is like a butterfly which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.”

It’s a fucking butterfly! Don’t. Fucking. Move.

I got off the subway. Don’t fall down the stairs, my brain said. Don’t. Fall down. The stairs.

There it is. The Upper Limits problem.

***

The upper limits problem is a concept I learned from the book Conscious Loving. I tell people about this book. I recommend it to friends. I buy it for friends. And of the entire book, the part I continue to re-read is the part about the upper limits.

The premise of the upper limits problem is: at some point during our childhood we made an association between feeling good and then, rather quickly, feeling bad. We were jumping for joy and babbling exuberantly and got told to keep it down; we brought home good grades and were told not to brag, etc. So at this point, most of us (not all of us, but it really does seem like most of us) unconsciously created a personal glass ceiling — we decided just how much good feelings we are allowed to have.

In the book, they put it this way: “Starting in childhood, most of us seem to put a lid on our positive energy in order to stay at the humdrum level of existence necessary to function in the workaday world,” wrote Kathleen and Gay Hendricks.

My upper limit is much lower than I’d like it to be. READ MORE…

JOMO, THE JOY OF MISSING OUT

horizontal on a dock in Edgewater, New Jersey. Mmm, the joy.

FOMO.

Fear.

Of.

Missing.

Out.

It’s a problem.

It’s especially a problem now, because now, more than ever, we know what other people are doing.

Back in the day, you used to have to write a letter. It could take weeks to get to them. More, if the rider got drunk or the horse was slow. Then, your correspondent would have to craft a response. By hand. With ink. The ink had to dry. They’d seal the letter with wax. Back in the saddlebag. Back on the horse. By the time you received that letter, they probably weren’t doing those things anymore! They could be pregnant! They could have died! You’d respond to their outdated news with news of your own that would be outdated by the time they got it. Ink to paper, paper in envelope, wax to seal. And again and again.

As recently as 30 years ago, you actually had to pick up the phone and call your friends. You had to ask them what they were doing. While asking them, you had to sit by the phone or stand in a phone booth. You didn’t make dinner. You didn’t do laundry. You didn’t commute. You put your body next to the phone and talked into it. You marveled at the miracle of hearing someone’s voice, perfect and seemingly in miniature, delivered directly to your ear. That voice could be thousands of miles across the country. Astonishing! You’d yell into the telephone because you could hardly believe the magic.

Even at the dawning of the interwebs, at least you had to send someone an email or schedule a date with them in a chat room. You wouldn’t see a photograph unless it was attached. And attachments could carry viruses, so you were careful.

Now, however, if someone’s at Burning Man wearing googoo goggles and an elephant trunk cock, you know instantly. You can see that so-and-so is snorkeling in Turks & Caicos. You’re aware that, at this very moment, a frenemy is on artist’s retreat in Laos, a friend is summiting a mountain, this one’s opening on Broadway, that one’s hitchhiking around Hawaii because that’s how people get around in Hawaii, and really it’s perfectly safe, isn’t that so cool?

We’re a digital culture of pseudo-stalkers. If we wonder where our friends are, we don’t even necessarily have to text them. Instead of communicating directly, we can just peek at their digital scrapbook. We can likely satisfy our curiosity in three clicks or less, without them even knowing.

We see what they’re doing without us. We know what we’re missing out on.

Or we think we know.

Just like with romantic relationships, nobody knows what’s actually happening on the inside of an experience — except the people inside it. Nobody knows the real dynamic except for those involved. And sometimes not even them! We don’t really know what that shiny award feels like because we cannot live for a single moment on the inside of someone else’s skin. Maybe they still feel like an imposter. Maybe they can’t shake the feeling that someone else was more deserving. We cannot hear anyone else’s thoughts as they think them. It might appear as though they are having the time of their life adventuring through the Middle East, but if you asked them with a little tenderness and curiosity, you’d find out that the trip has been a bone-chillingly lonely night of the soul. To know for certain — as much as we can know anyone else’s experience through words — we still need to ask.

Recently I texted a world-traveling friend, “It looks like you’re killin’ it!”

“Just out of curiosity,” he replied, “what makes it seem like I’m killin’ it?”

His Facebook posts, that’s what. His sublimely epic photography.

Facebook image crafting. That is its scientific name. I saw a meme the other day that sums it up beautifully:

“Don’t forget to pretend to have your shit together for strangers on the internet today.” READ MORE…