Image by Robyn Sky. Winter 2018

108. listening about race: horizontalism with lila

In this episode, I lie down with myself. I share: * the WOC Podcasters solidarity statement * my personal commitment to ongoing anti-racist action * the names of a few of the many Black lives lost to police brutality, and: * the story of that time I didn’t talk about race (for 11 years) and how that is a textbook example of white fragility and privilege *** I stand with my sisters from the WOC Podcasters Community, lead by Danielle Desir and crafted by change-maker Tangia Renee [TAN-gee].

Hello horizontal lover.

Greetings from Bali. You’ll probably hear jungle sounds throughout the course of this episode.

Just like my other episodes, let this one move you.

Perhaps unlike my other episodes, please let this one move you to action.

I stand with my sisters from the WOC Podcasters Community, lead by Danielle Desir and crafted by change-maker Tangia Renee. These are Tangee’s words. These are our words:

We are podcasters united to condemn the tragic murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many many others at the hands of police. This is a continuation of the systemic racism pervasive in our country since its inception and we are committed to standing against racism in all its forms.

We believe that to be silent is to be complicit.

We believe that Black lives matter.

We believe that Black lives are more important than property.

We believe that we have a responsibility to use our platforms to speak out against this injustice whenever and wherever we are witness to it.

In creating digital media we have built audiences that return week after week to hear our voices and we will use our voices to speak against anti-blackness and police brutality, and we encourage our audiences to be educated, engaged, and to take action.

That concludes the statement crafted by the WOC Podcasters Community. The rest of these words are my own.

Here are things I have learned this week:

It is not possible to be not racist. Therefore, I must be ANTI-RACIST, and seek to excavate racism in myself as I fight it outwardly in my society.

Being an ally is not enough. I must stand in SOLIDARITY with Black people, Indigenous people & People Of Color, and that means ACTION.

Action means RESOURCES. TIME. MONEY. ENERGY. WORK.

There are many ways to take action, and all of them must be done. They cannot all be done at once. I must settle in for a lifelong battle in order to be in SOLIDARITY with those that I love, who can’t escape this battle.

Since they can’t escape, I must continue to STAND UP, with all this privilege that I have not earned.

I will NEVER feel like I am doing ENOUGH. But that is EXACTLY THE REASON TO CONTINUE.

Here are all the things I have written in all caps:

ANTI-RACIST

SOLIDARITY

ACTION

RESOURCES. TIME. MONEY. ENERGY. WORK.

STAND UP

NEVER ENOUGH

EXACTLY THE REASON TO CONTINUE.

I want to make sure that my participation in social justice activism is sustainable over the course of my lifetime, and not something I only do now, while the news cycle is hot.

For myself, I’ve identified 8 types of action to take, and I’ve written them here as imperative verbs:

- Study.

- Self-examine.

- Donate.

- Advocate.

- Amplify.

- Educate.

- Cherish.

- And Celebrate.

Here are a few examples of what each of these can look like for me:

I can STUDY by reading books like Reni Eddo Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race and Layla F Saad’s Me and White Supremacy and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.

I can SELF-EXAMINE by sitting with, meditating on, and journaling about the white supremacist brainwashing I’ve excavated in myself. I can join a small private group in which white people will reckon with our privilege, blind spots, and activism together — the one I’m in is called “Get to Work: antiracism support for white allies” — and then I can marinate on and write about the topics we discuss.

I can DONATE by setting up an ongoing donation (which is exactly what I have done!) to an organization like my personal favorite podcast, Ear Hustle, which makes marginalized voices HEARD, from both inside and outside the prison system— many of them Black, most of them People Of Color. When you hear this podcast you’ll be participating in one of the most crucial anti-racist actions — LISTENING to the experiences of People Of Color.

Follow my lead, and / or contribute to other organizations that make marginalized voices heard, that protect black & brown bodies, and, if you are white, that uplift people who do not look like you. As a fellow white person, do your part by redistributing some of the wealth you got from participating in a system RIGGED FOR YOUR BENEFIT. Two other worthy organizations you might consider pledging your ongoing financial support to are:

and

the NAACP — the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

I can ADVOCATE by voting for people who value the lives of BIPOC — Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. I can advocate by going to a protest, phoning my government representatives, and using my social media power for activism, letting the people in my web know how they too can take action.

I can AMPLIFY by using my horizontal platform to interview even more BIPOC guests and broadcast their stories to the world. (I do. And I will.) I can re-post content created by BIPOC Sex Educators, artists, and Social Justice Warriors.

I can EDUCATE by leading discussions among my white friends and family about racism and social justice, by calling out microaggressions I see on social media, shouldering some of the burden of that emotional labor. I can say these words — from a script written by the author Kat Vellos, in her guide titled “How You Can Support Your Black & Non-Black Friends Right Now,” “Will you join with me to make a long term commitment to working on dismantling racism in the world and in ourselves?” And, “Will you hold me accountable and bring it up to me when I stop being focused on this?”

I can CHERISH the BIPOC people in my life by loving them in the way that they wish to be loved. Making sure I know their love language, and acting on it.

And last, but of vital importance, I can CELEBRATE the accomplishments, contributions, triumphs, art, and scholarship of Black people in this world.

I can CELEBRATE the advancements of this revolution as, in the [Theodore Parker’s] words, made popular by MLK, “the arc of the moral universe” […] “bends toward justice.”

I can CELEBRATE by following organizations like Good Black News & spreading the word.

Study.

Self-examine.

Donate.

Advocate.

Amplify.

Educate.

Cherish.

And Celebrate.

I don’t have a neat acronym. SSDAAECA.

I’ll have to work on that.

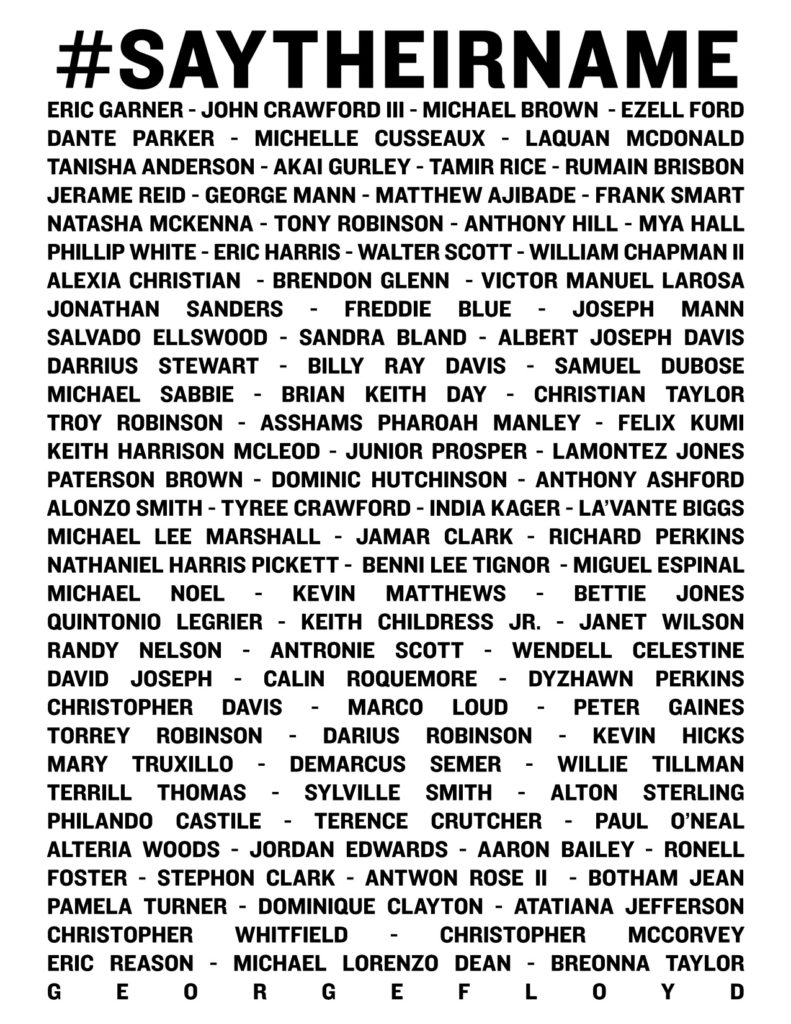

What follows now is an incomplete, non-exhaustive list of Black people who have been killed by police brutality. Stay with me through this. Hear the names. Know that these are only a few of them. Repeat them after me. This can be our version of a candlelit vigil.

This list comes from NPR’s Code Switch podcast, which broadcasts fearless conversations about race. I’ve added the name of Tony McDade, a trans man, as trans folx are at even higher risk of being targeted, and yet receive far less attention from the press, as well as the name of Maurice Gordon, who was shot by an officer while waiting for a tow truck, has received minimal press, and whose death illustrates the great risk in Driving While Black, and the names of Aiyana Stanley-Jones and Pearlie Golden, killed in their own homes, who have not become household names, as there continues to be a lack of mobilized outrage at the deaths of Black women.

After I read these names, I’ll tell you the story of how I didn’t talk about race for 11 years, and how that is a textbook case of white fragility and white privilege.

Maurice Gordon

Aiyana Stanley-Jones

Pearlie Golden

&

Tony McDade

This story is from my email missive dated July 26th, 2016. It is as true now as it was then.

Dear Ones,

This is the second time in my life I have written about race.

There was a period — of about eleven years long — in which I didn’t even mention race, because I felt too ashamed.

From the time I was one year old until my parents got divorced when I was twelve, I grew up in a town called Freeport, Long Island. Freeport was the full-on suburbs, but an integrated community. I went to elementary school, middle school, and the first year of junior high with kids of all races. I played kickball with the Latin-American kids down the street (when they would let me).

My parent’s close friend, our next door neighbor Pat, was a Jamaican lawyer almost too busy with her studies and work to socialize, but we got to spend time with her once in a while, and she always had a kind word for me and let me stop by for visits.

When I was in first grade or so, I had a kind of love quartet (do you think? one more than a love triangle?) with a girl I don’t recall and two boys, Harry (who was Latino) and Khoury (who was black). I vaguely recall one of them sticking a note of mine down his pants.

Young love.

It’s not that I “didn’t see color.” I definitely noticed people’s skin. Most of all, in seventh grade, I noticed the skin of a girl called Kristy, who was both black and white and had skin of coffee and cream. She was the captain of my cheerleading squad, the most popular girl in school, and I wished I could be just like her.

I’m reminded of a hashtag my Facebook friend Kofi Opam often uses, #everybodywannabeblackbutdontnobodywannabeblack.

Kristy wore an oversized puffy boy’s jacket with the name of a sports team on it, so I begged my mom to buy me one too. I chose my team by the colors I liked best, and that is how I came to choose the Charlotte Hornets. This is what they call a “poser.” That was among the many things my schoolmates called me that year. One day, a strong older black girl let it be known that she was going to beat my ass after school. I’m not sure what I did to upset her. (Happily, I did not get beat up. When the time came, she was nowhere to be found.)

After my parent’s divorce, my mother moved us down to Seminole, Florida. Something was off-kilter and unsettling on my first day of eighth grade, and I didn’t figure it out until I looked at the expertly “tanned” skin of everyone around me. Save approximately two Asian people, they were all white. Seminole, Florida was one of the whitest neighborhoods in the world. Probably still is.

Eighth grade rivaled seventh grade for the worst year of my life so far. At least in seventh grade I had a few outcasts to sit with at lunch. In eighth grade, once my little trio of Wicca dabblers turned their backs on me, I ate lunch in the bathroom for a good while until I fell in with the Baptist kids, who really wanted to save my soul but had little interest in being my friend. Those white children were some of the meanest people I’ve known.

In high school I understood why Seminole Middle School was so white. I recognized the residual damage of segregation, and the paltry attempts towards desegregation as I was bussed-in to a (mostly Black) high school in St. Petersburg — Gibbs High School — forty-five minutes from my house to attend a (mixed race) magnet school arts program, Pinellas County Center for the Arts. We had a few core curriculum classes that mingled us with the Gibbs students, maths and sciences and driver’s ed, and of course, lunch, (which I opted out of when my acting teacher allowed us to eat in her classroom) but we had an extra hour of class each day, so our program was almost entirely separate. We rode different buses.

My closest black friend in high school was the child actor Marque Lynche. We traded massages nearly every day. I was pretty sure that Marque wasn’t interested in women, so I don’t think I ever made my little crush known. To this day, there’s no one (and I have received many a professional massage) who has made my body tingle like Marque did, just by squeezing my shoulders. He smelled so good, something like almonds and sugar – marzipan, maybe. His skin was dolphin-smooth. (Or really, what I imagine a dolphin’s skin to feel like, as I’ve never swam with one.) Marque was more than a little bit famous, and I admired him for having already been on television while the rest of us were doing plays at the rec center. He had this suave confidence and style, so unusual for a high school student. I never could discern if he actually felt that self-assured on the inside. A lot of the other students felt that he was too full of himself. They talked about that huge chip on his shoulder. There was a little chip there. But I massaged it every time I saw him. Come to think of it, my connection with Marque is probably the reason I went on to practice Thai massage. Marque had, as they say, a magic touch. He’s dead now. I don’t know how. I learned about it on the internet. The articles were very vague.

I graduated my arts program and came back home to New York for college. I studied Drama at NYU. It felt like home and I was happy to have the world’s diversity present in my daily life, on every subway ride. I felt I belonged with the city.

In my freshman acting class, I began to become friends with a brilliant tap dancer looking to make a transition into acting, a black man with beautiful twisted dreads in a pattern that looked like a romanesco. We enjoyed each other’s company. We sat next to each other. We hung out outside of class. I had the sense that he might be romantically attracted to me, and though I didn’t feel the same way about him, I didn’t bring it up because I didn’t want to lose him.

One day during freshman year, our German acting teacher Saskia conducted a slam poetry acting exercise. I felt extremely ungainly and unskilled, all prickles and nervous sweats. On my turn, the only thing I remember saying was, “I don’t feel like I can slam because I’m not black, and I’m not black, I’m not.” Surely I was in the hot seat for longer than it took to say those words, but those are the only words I remember.

Matthew essentially never spoke to me again.

Those are the words I remember, because those are the words that lost me my friend.

At that time, I didn’t yet know terms like Driving While Black, systemic racism, or intersectionality.

Sophomore year, Matthew and I were assigned to work together on a scene. I was also taking classes on Multicultural Women Playwrights and Sex & Gender. I was starting to learn. I tried to broach the subject the first time we met for rehearsal in my dorm’s common room. I said something like, “I know you haven’t been comfortable with me since that slam exercise in class last year. I think if we’re gonna to be working together we should probably address that.” He said that there was nothing to talk about.

I said, “Do you think I’m racist?”

He said, “No, I just think you’re ignorant.”

“Okay, I responded, “then why don’t you educate me?”

“Because that’s not my job,” he replied.

I had nothing to say to that, so we just rehearsed the scene.

Then I didn’t talk about race for a decade.

I imagine that I am not the only white person with great love for people of color in my heart who has, cloaked in privilege and shame, remained silent for years while our friends prayed and fought and ran and donned suits for their lives.

This is from a post I wrote at 1am on December 17th, 2014. That was the first time I wrote about this:

I didn’t talk about race until November of 2013, when I performed in Amina Henry‘s brilliant, heinous play An American Family Takes a Lover, in which I played one of the most vile characters I have ever come across — an emotionally, verbally, physically, and sexually abusive wife of an emotionally, verbally, physically, and sexually abusive husband, who kidnap a young black woman from a grocery store and make her their modern-day slave. I was unsure that I wanted to take the part, because I didn’t know if I wanted to go into the abyss like that. The way Kira Simring, our director, finally was able to help me navigate myself into the part, without nausea, was to tap me into how stylized I could make the character of Lady Anne. This took the character away from my voice and made her like a storybook witch. Still, the way my character treats Justine is unpalatable.

Tiffany Nichole Greene did one of the bravest acting feats I have ever witnessed, allowing herself to experience the terror, rage, anxiety, self-loathing, hatred and numbness of Justine. During the process, I asked her how she was doing, and she told me that nobody had asked her that, and she was grateful that I asked, and that it was really hard.

I thought maybe audience members of color would be angry at me, because they hated my character. The opposite was true. Many many members of the audience (including men that Amina had worked with through an arts program in a prison) came up to shake my hand or hug me and say, “I hated you! Well done!” In fact, the only person I got word of that conflated me with my character was a white friend of a friend who said that he wasn’t sure he wanted to meet me because he couldn’t imagine that I wasn’t mean.

After each show, for the first time in my life, I went out with a group of diverse people and actually talked about race, injustice, sexism, oppression, legacy, and inequality. It was a relief to speak about it openly, with people I have so much affection for, kind, talented, luminous people. People that I didn’t feel afraid would hate me for the genetic accident of my skin color. People that I didn’t feel afraid would turn their back to me if I proved to be ignorant.

This is when I first got to meet and share deep feelings and time with Celestine, Dennis, Lori. I listened a lot. I will listen more. I am reading.

I am listening.

I intend to be an ally. If you see that I could be doing that better, please tell me.

I would find it very meaningful if you did not turn your back on me in my ignorance. I love you. Your life matters to me. You matter to me.

I have done a lot of reading since then.

A brief reading primer:

-

- If you’re uncertain of the meaning of the phrase “unearned privilege,” please read “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack“

- If you wonder about racist blind spots, please read “28 Common Racist Attitudes and Behaviors” (I feel particularly schooled by this one.)

- If you wish someone would give you a guide, here is one, “10 Simple Ways White People Can Step Up to Fight Everyday Racism“

Lori J. Laing wrote this post on Facebook a bit ago, and it has been vibrating in my heart since:

“I don’t think enough white people talk to each other about how fucked up their community is. And this IS about a sickness in the white community. I think the best thing white people can do in the wake of these tragedies is talk to other white people about what the hell is going on. I mean, if you really care. Don’t sit around and boo hoo with black people trying to sympathize. Get you another white person and figure out what the hell yall are doing wrong and how you can help more (white) people in your community find their humanity.”

As I best understand it today, here is the responsibility of the privileged and aware person:

TALK ABOUT RACE. (Your loved ones of color can’t ignore the topic.) (For that matter, make sure you HAVE LOVED ONES OF COLOR.)

Better yet: LISTEN ABOUT RACE. EXAMINE YOURSELF. Choose to act from LOVE INSTEAD OF GUILT.

When someone tells you they’ve been discriminated against, BELIEVE THEM.

In the event that you witness injustice, SPEAK UP and CALL IT OUT.

When you hear a racist comment, say THAT’S RACIST.

And, if you can find the bravery, BE THE SHIELD between hatred and human.

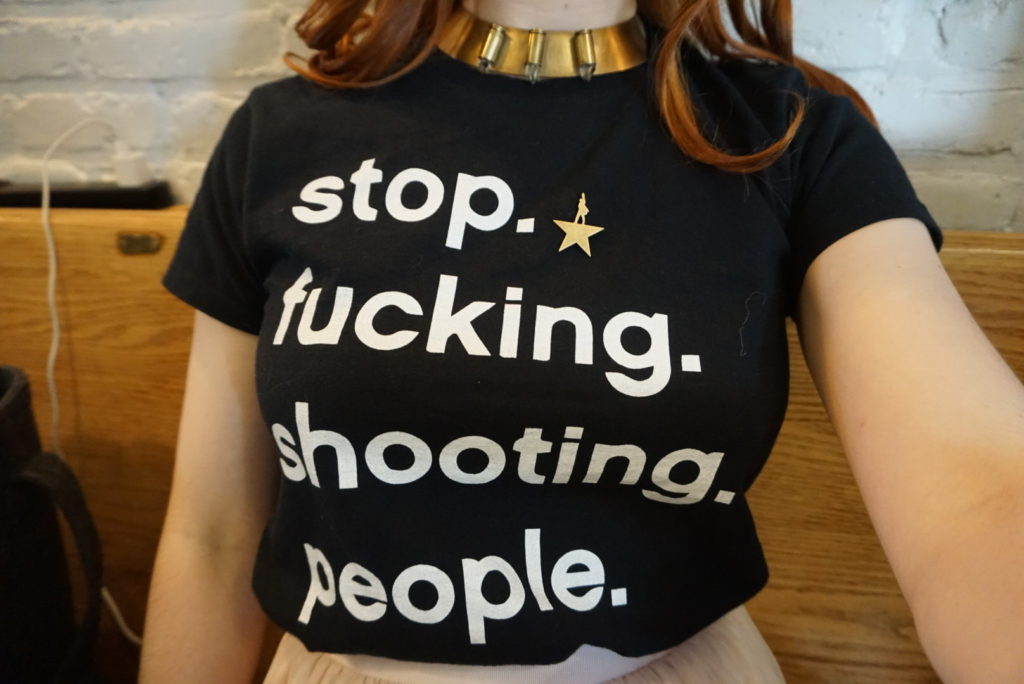

Because of my unearned privilege, I can wear that t-shirt you see at the top of this missive. I can wear a message of protest emblazoned across my chest without fear of being shot. I can say things that it is dangerous for my loved ones of color to say.

Williamsburg, 2016.

That means it is just, it is right, it is fair, that I should take it upon myself to say those things.

Since people who look like me have oppressed people who don’t look like me and are still suffering in great numbers, it takes people who look like me Standing Up and saying This Is Unacceptable to truly dismantle the system.

It will take men to dismantle patriarchy.

It will take white people to dismantle systemic racism.

It will take cisgendered people and “straight” people to dismantle transphobia and homophobia.

The sickness is with the oppressor and those who benefit from the privileges of the oppressors and it is we who must learn and fight.

I witness white people turning away from conversations about racial matters all the time, because the subject makes them uncomfortable. There is an academic term for this. It’s called white fragility. Consider this sign held up by a white protester, photographed, (re?)posted by Spike Lee, which read “Black Lives Matter More Than White Feelings.”

[Note: Didn’t find the original photo. Here is one from around the same time, circa 2016]

From the 2016 article “On the Ground at the Black Lives Matter Protest in Union Square“

I think what my fellow white people who “don’t want to talk about it” are really expressing is that they are unwilling to be heartbroken for people of color and the lengthy history of horrendous acts that have been perpetrated on people of color. By someone who looks white.

But our feelings are RESILIENT, my fellow white-lookin’ people, and being heartbroken is CORRECT. It is a proper response to the maelstrom of injustice permeating our society.

And then the question is, what do you do with your heartbreak?

Do you stop reading the news and scrolling through your social media feed because it’s too much of a bummer?

Do you try to numb yourself with: alcohol, drugs, food, sex, expensive things, bars on your windows, electricity on your gates?

Do you content yourself with the belief that they are not coming for you?

Remember Pastor Martin Niemoller’s poem:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

My friend Deborah said to me the other day, “I’ve been living with this for thirty-one years. I don’t know if tomorrow my brothers will be alive. My mother. Myself.”

And my heart broke again.

And it is capable of breaking again and again.

Heartbreak can be the most combustible catalyst.

Let’s figure out ways to share the burden of heartbreak that people of color have had no choice but to carry for generations. I believe in our ability to learn to, as Stephen Jenkinson puts it, “carry our grief.” I deeply feel Jenkinson’s belief that grief can never be vanquished, it can only be carried.

Jenkinson says, “Grief is not a feeling; grief is a skill.”

Now more than ever we must become practiced in the skill of grief so that it doesn’t paralyze us. Our grief must not keep us from doing the work that needs to be done in our lifetimes.

We must use our privilege to dismantle this horrible, horrifying system.

***

One magical day last September, I decided to take an adventure up to my friend’s empty house in Woodstock. I knew that it was a forty-minute walk from the bus stop, but I decided that I’d figure that out later. I had to get a sandwich or face hangriness so I picked one up and very nearly missed the bus. I slid into the line with five minutes to spare, panting, and this beautiful Black man in front of me turned around, flashed me a huge smile and said, “We made it!”

“We did,” I said, “And I got a sandwich!”

“And I got to swim,” he said.

I recognized his accent and said, in Portuguese, “You’re a capoeirista, aren’t you.”

“I am,” he answered in Portuguese, and we were off.

It turned out that he was heading upstate to perform with his students in a site-specific multi-disciplinary dance piece at Opus 40, a site of forty years of handcrafted stone work performed by one man. He invited me along. We were picked up in New Paltz by a nice old hippie musician lady, and I spent the day watching all these lovely children dance on art. At the end of the program, we chanted a song that the camp-leading hippie couple had written back in the 60s. I thought it was pretty cheesy. It went like this:

May peace prevail on Earth

And let it begin with me

We celebrate the birth

Of joyful harmony

May peace prevail on Earth (May peace prevail on Earth!)

May peace prevail on Earth (May peace prevail on Earth!)

Now I hear it differently, and I think it is profound. I hear Prevail, may Peace PREVAIL on Earth, and let it BEGIN WITH ME.

Big Love,

Lila

That’s the end of the email I sent in 2016.

I do not think I have done enough for the cause since then.

I am committed to doing better.

Finally, here’s the last line of a letter I wrote to a young listener, a woman who had joined the ranks of the heartbroken.

“What will you do,” I asked her, “with all that empathy?”

And now I ask you, dear ones, horizontal lovers, Intimacy Warriors:

What will you do with all

your

Empathy?

P.S. Matt Stillman, beloved horizontal guest [of episodes 30. my heart is broken may it never heal, and 31. the skull story] and my dear friend, just brought to my attention that horizontalismo, in Spanish, or horizontalism in English, is a movement of mutual aid, most prominently publicized in Argentina, that exists when governments fail to take care of their people. I’ll be learning about ways that I can extend my horizontality into horizontalism.

In next week’s episode of horizontal, I lie down with Kai Mata, Indonesia’s openly queer, rainbow-toting singer-songwriter. It’s still very dangerous to be queer in Indonesia. We will celebrate her bravery with the next couple of episodes.

Until then, may you love people.

May you love people and let them know.

May you fight the good fight and, in the words of Cornel West, “Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public, just like tenderness is what love feels like in private.”

Thank you for getting horizontal-

ism.

108. listening about race: horizontalism with lila

In this episode, I lie down with myself. I share: * the WOC Podcasters solidarity statement * my personal commitment to ongoing anti-racist action * the names of a few of the many Black lives lost to police brutality, and: * the story of that time I didn’t talk about race (for 11 years) and how that is a textbook example of white fragility and privilege *** I stand with my sisters from the WOC Podcasters Community, lead by Danielle Desir and crafted by change-maker Tangia Renee [TAN-gee].